FROM FOREST TO FRAMEWORK

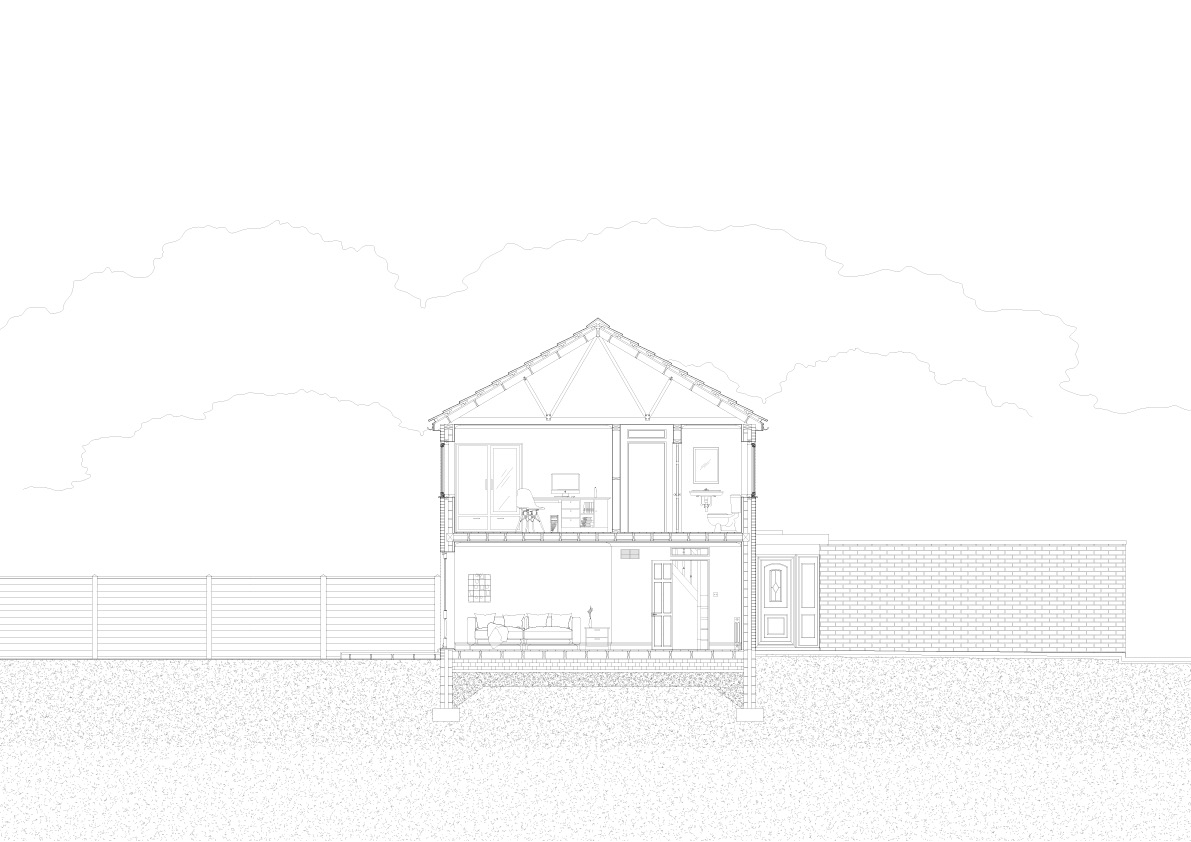

Fith year: Diploma 13 thickness 2024-25. Fairfields, Thetford town, Norfolk, United Kingdom

Description:

In this project I explore the localized application and distribution of timber from Continuous cover forestry to retrofit houses in Thetford town. Historically, the materials that built our homes have been local, visible and recognizable; today we live in homes disconnected from their material origin. My aim to is to re-establish this connection, through Thetford forest- an example of a plantation taking steps towards mixed species stands, and Thetford town, a town in close proximity; a typical post war English settlement.

In this project I explore the localized application and distribution of timber from Continuous cover forestry to retrofit houses in Thetford town. Historically, the materials that built our homes have been local, visible and recognizable; today we live in homes disconnected from their material origin. My aim to is to re-establish this connection, through Thetford forest- an example of a plantation taking steps towards mixed species stands, and Thetford town, a town in close proximity; a typical post war English settlement.

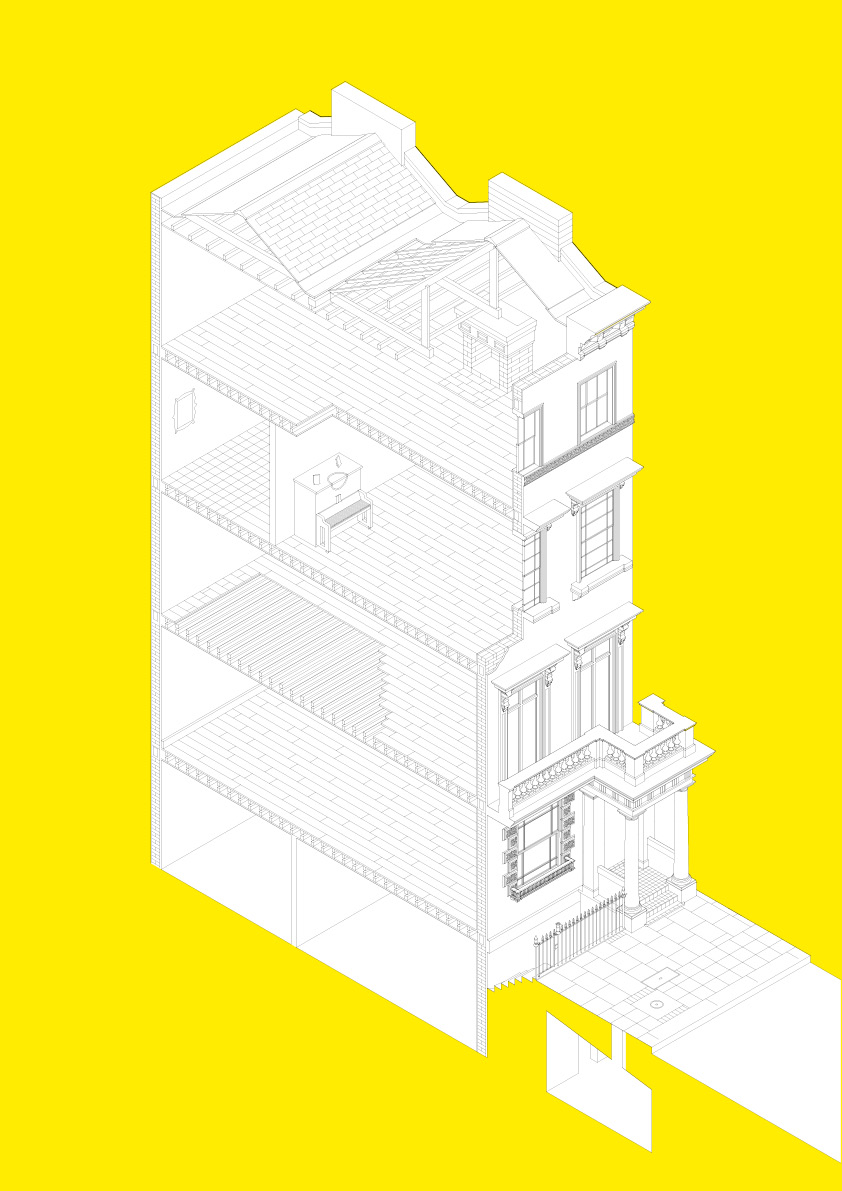

In the early 19th century, London was a city on the rise. Growing into one of the largest cities in the world, at the Centre of an expanding British Empire. This period, fuelled by the Industrial Revolution brought an explosion of urban growth and housing demand. As new homes appeared to accommodate the surge of people moving into the city the terraced house was born—a design tailored to meet the needs of London’s growing middle class.

An example of this historical disconnection can be observed through the coal hole, an opening in the pavement that allowed coal delivery directly into underground bunkers. This practical design facilitated the heating of homes during a time when coal was the primary energy source. The coal enters through a hatch, connecting to basements that housed kitchens, fireplaces, and servant quarters— the essential elements that made these homes liveable. The coal hole has become a metaphor for spatial and social hierarchies, as the multiple layers in play represent spaces of function and class separation, whilst also exploring hidden labour and material flows. This object, which has since become obsolete in its function, a historical machine that hides the mechanics of comfort; discreetly separates the messy delivery process from the affluent homeowners, who benefit from it without direct involvement. This separation between source and comfort is also mirrored in the construction of homes, in which we as the occupiers are unaware of the origin and complexities of materials that make the home, as such this globalized material network further separates and subsequently ‘hides’.

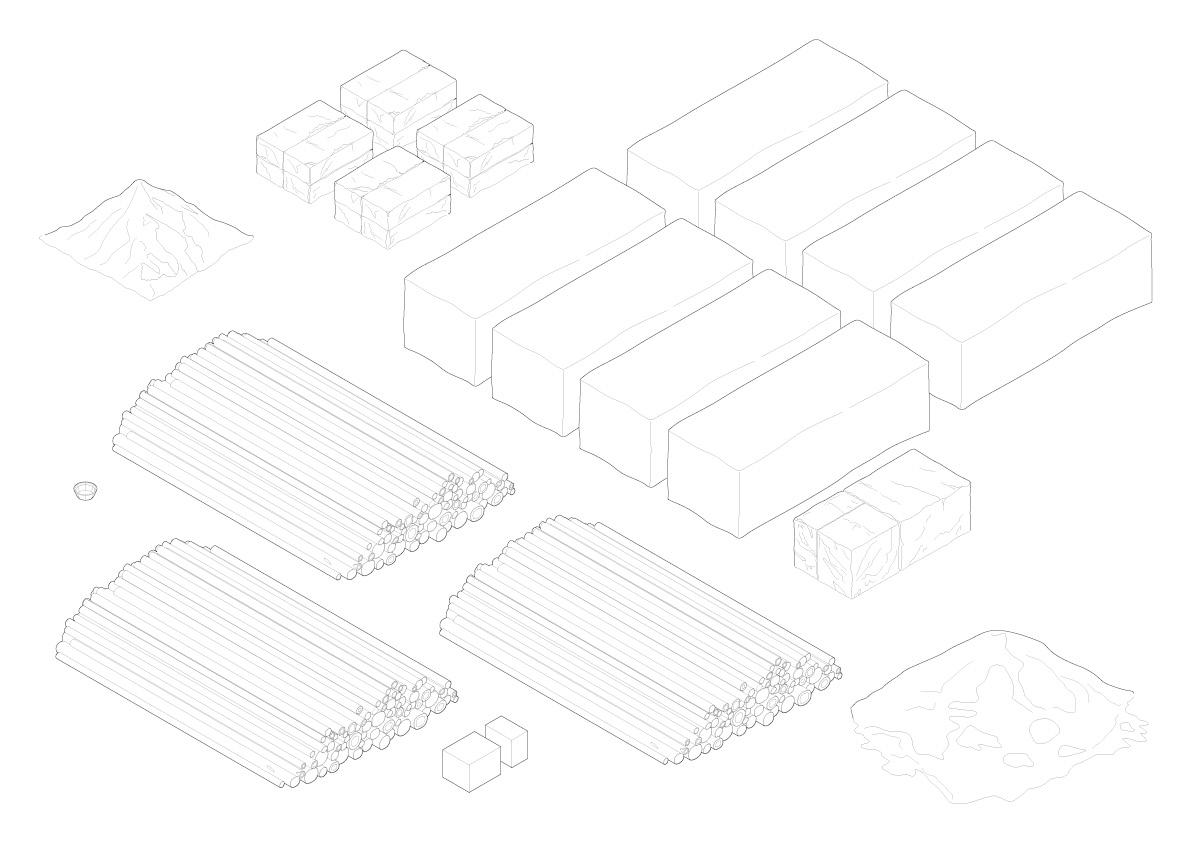

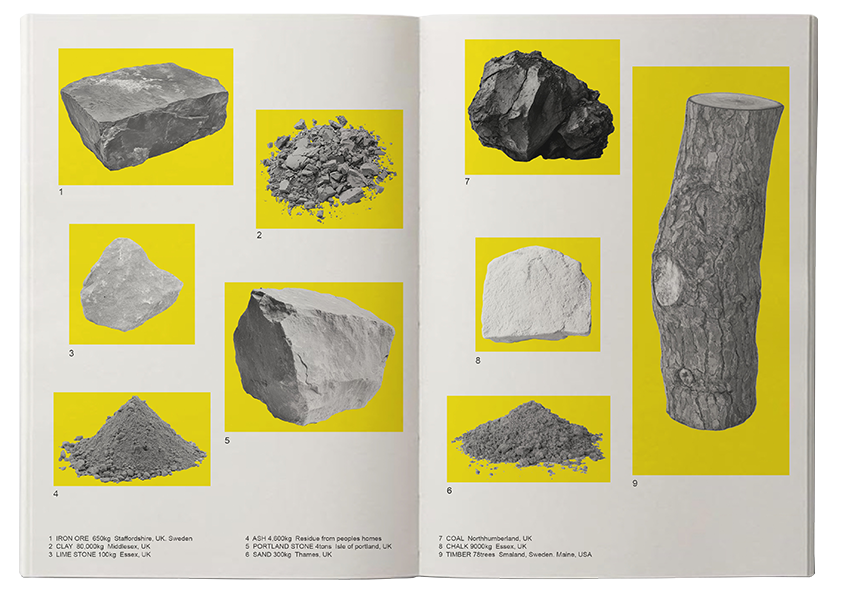

This idea of distance of separation prompts a deeper investigation into the materials within these homes. How far did each component travel to become part of the building? What journeys did they undertake? By deconstructing a typical Regency house, I trace the origins of its materials—timber, brick, stone, and coal— and the journeys they undertook to become part of the home revealing not only the physical distances between us and our built environment but also the social and ecological implications of material extraction and consumption.

The Industrial Revolution marked a turning point for forestry, the introduction of steam-powered machinery and sawmills revolutionized timber production. Plantations, typically consisting of fast-growing species like pine, were designed to maximize efficiency. By planting a single species in uniform rows, foresters could streamline harvesting and processing. This approach was further reinforced by economic incentives, as monocultures allowed for easier management, higher productivity, and greater profitability compared to diverse, natural forests. However, monoculture plantations come with significant environmental costs.

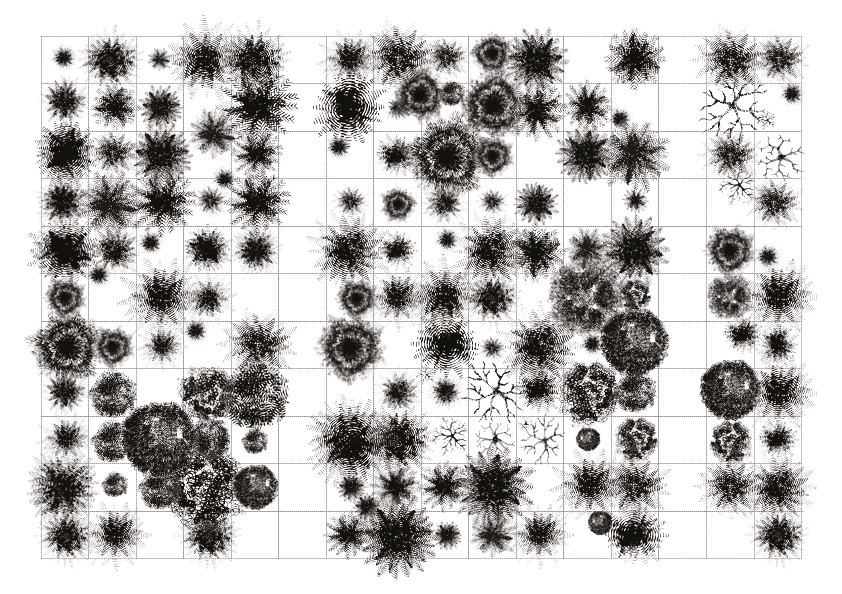

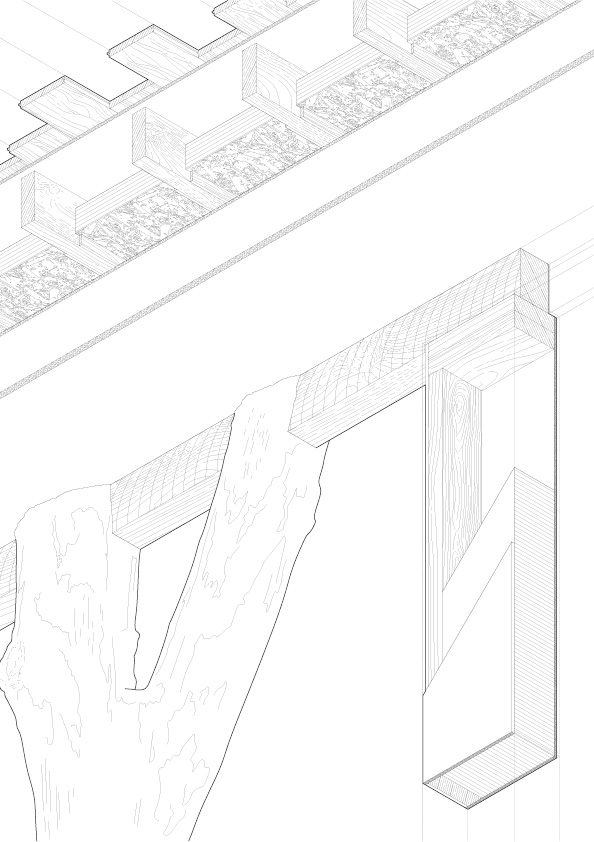

Today, the focus is shifting toward sustainable practices like continuous cover forestry (CCF), which prioritizes biodiversity and resilience. This gentler forest management technique focuses on maintaining a continuous tree canopy. The process is designed to mimic natural forest processes, allowing natural regeneration without the need for clear-cutting or replanting. Over time, the forest evolves into a multi-layered, multi-generational system. This mixed-species competition alongside natural regeneration allows the trees to develop irregular forms.

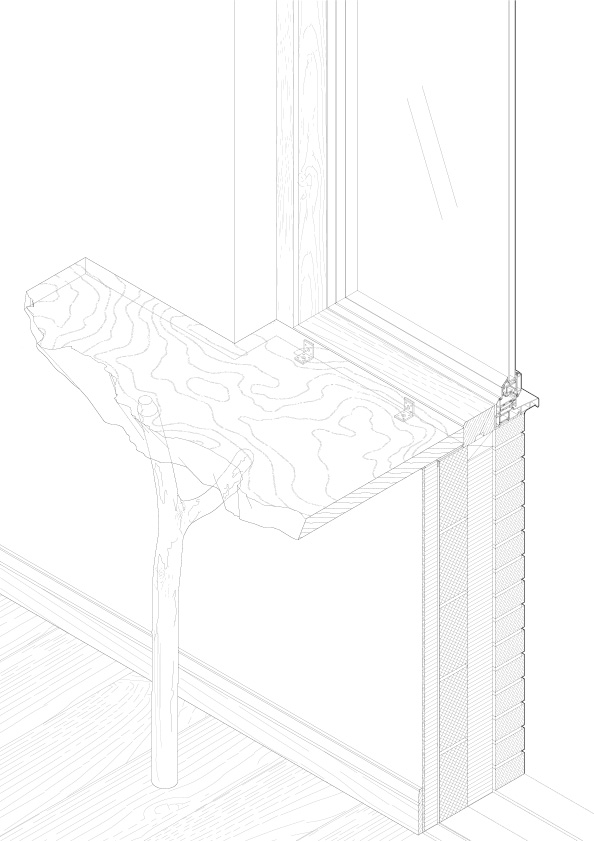

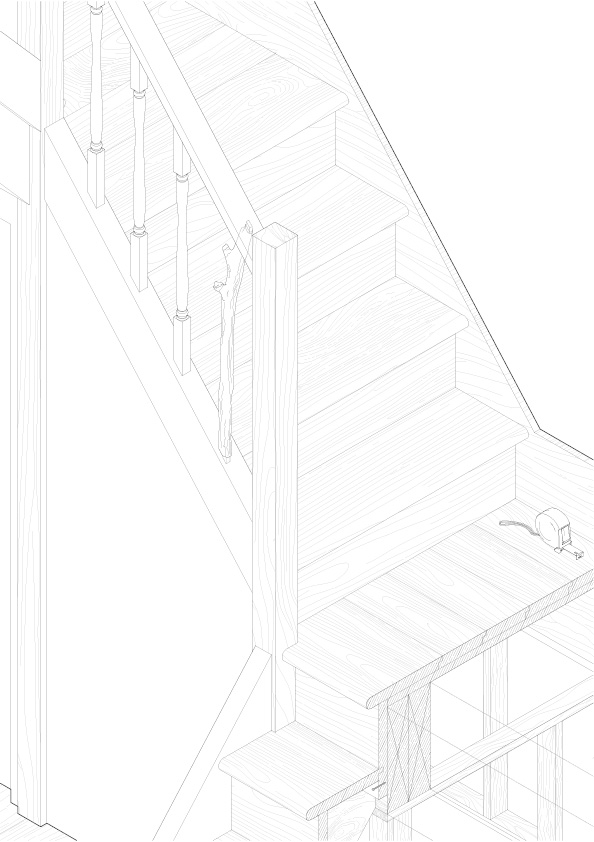

Plantations are grown for straight, fast, uniform timber, these are cut on site to standard sizes. So when I say irregular, this can be defined as consisting- Heavy knots, forks, heavily tapered, curved stem, spiral grain, reaction wood, bark inclusion and Crooks. This goes in hand with sawmills definition of irregular or unusable timber, these mentioned irregularities behind the wood creates challenges for the automated standard systems of sawing to process. Trees always grow for strength and balance, growing in a structurally rational response to forces, So every branch, every, curve every fork is a structural rational response to forces such as wind, light and gravity. this means their imperfections are optimized for strength and balance in their natural context. I look at bringing the forest back into the house. The site i have chosen within Thetford town is housing at Fairfield. I look at how I can incorporate ‘irregular timber’ to retrofit these homes. I observe the frequent remodeling of these sites, from altering layouts to building extension. Through this I see the vast opportunity for both small and large on site interventions ; A broken banister post replaced with a juvenile trunk, breaking the regular repetition. A window sill, made from a thick, curved timber offcut extends into the room — becoming a seat, a shelf, or a desk. An opening of an internal wall, aided by a tree fork cut to shape around the ceiling beam. So the project explores a construction methodology rooted in the principles of Continuous Cover Forestry (CCF). Homes can be materially and structurally shaped by the forest, and in turn, a demand for timber that supports the expansion of CCF in Thetford. So really to summarise , the industrial view is that its unusable, problematic, however the material reality is that the irregularities are created through structural evolution, my view is that its expressive structural, beautiful and full of potential.